How Language Shapes the Way We Think

Episode 36 of Wild Geese Podcast

🎙️Watch the episode on Youtube, Spotify, or listen on Apple 🎙️

🌀“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein🌀

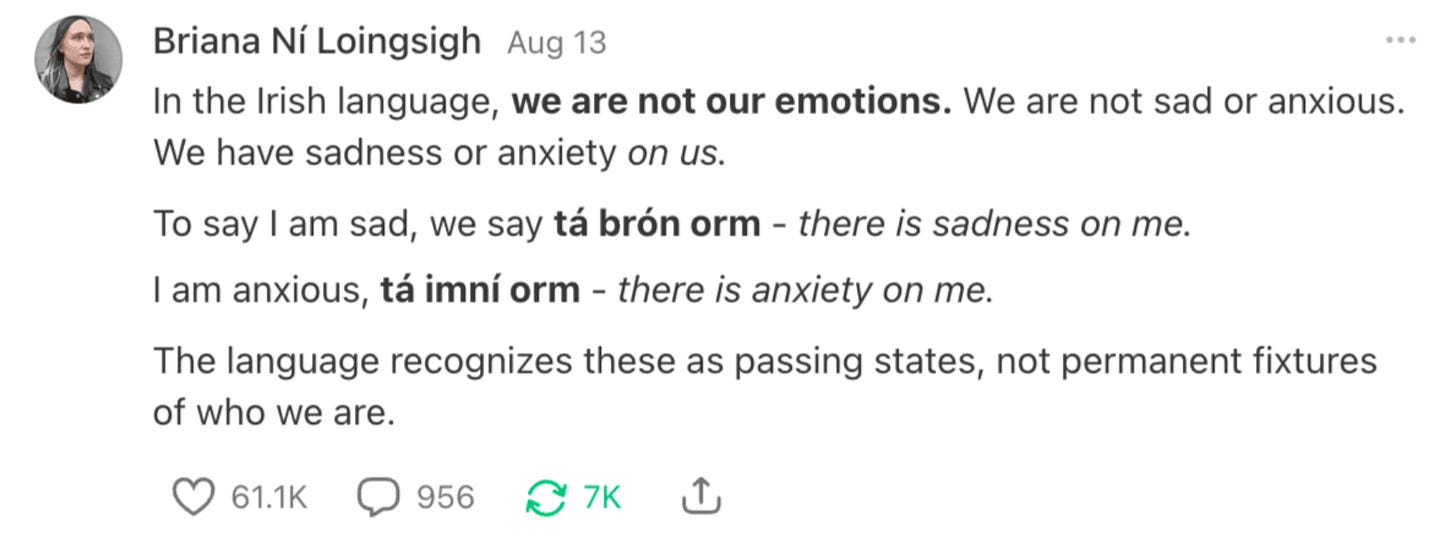

The English language often feels like it’s trying to compartmentalize people into static identities. In the past few months, I’ve had this conversation with multiple people in different contexts. Whether we’re talking about our emotions or attachment styles, there’s an over-identification with passing states that seem baked into the way the language is used.

It’s “I am sad,” not “I am experiencing sadness.”

It’s “I am avoidant,” not “I am engaging in avoidant behaviors.”

It’s “I’m hungry,” not “I have hunger.”

I’ve started to feel uncomfortable with this, and that’s coming from a woman that used to be obsessed with personality quizzes. When I was younger, I was constantly reaching for something outside of myself to tell me who I am. But with each passing year, it’s clear to me that I am constantly changing, and I’d like the words I use to reflect that flexibility.

For this reason and many others, I believe my worldview is dramatically limited by the fact that I only speak English. Luckily, we are not static beings. I have the capacity to learn from the wisdom of languages I don’t yet speak, and so do you.

I believe Indigenous languages hold deep wisdom that can liberate us from constraints on our personhood. But beyond our individual selves, they can also show us how to be in deeper community with each other. And by each other, I don’t just mean other human beings. I mean beings that the English language don’t even recognize as “beings” at all.

The Irish language is endangered, but Foghlaimeoir is doing her part to keep it alive here on Substack. The post below really helped to crack things open for me in this episode.

Conceptual Metaphors in the English Language

I loved this essay by

. She’s really focused on the way a writer’s use of metaphor may key you into their entire worldview. She quotes George Lakoff and Mark Johnson Metaphors we Live By to focus on three prominent metaphors that are so baked into the English language, we may not even recognize them when they’re used: argument is war, time is money, and status is height.The time is money metaphor reminded me of another post by Foghlaimeoir about the Irish proverb “time is a good storyteller.” There are so many examples like this, where I feel like I can see a worldview peaking through a different language. Money and stories flow very differently. How might I perceive the world differently if I spoke of time in that way?

Of course forces of colonization want me to think my time is something to sell. But I think when we can start to see these languages that have been systematically killed off as doors to a different way of seeing the world (versus just a group of vocabulary words), we can start to understand why they might want to silence a differing perspective.

The Power of Language

Griffin’s Tiktok puts it so beautifully. After discussing the ways legality and morality get conflated to justify crimes against humanity, he says “ the state has the power of violence, but language has the power to normalize it. And we need to be very conscious of that power.”

Calling a person “an illegal,” and flattening their entire existence into a crime is dehumanizing. But it doesn’t stop at a social slight, language like that is propaganda that drives public opinion to the point where they think it’s justified for their neighbors to be disappeared off the street by ICE.

We have a responsibility to use the language we speak in a way that doesn’t turn violent. The necessity to do so is in the etymology of the word “culture” itself.

Edward S. Casey wrote, “The very word culture meant ‘place tilled’ in Middle English, and the same word goes back to Latin colere, ‘to inhabit, care for, till, worship’…To be cultural, to have a culture, is to inhabit a place sufficiently intensely to cultivate it—to be responsible for it, to respond to it, to attend to it caringly.”

I think the nature aspect of this metaphor opens it up to not just the people around you, but the place around you.

The Grammar of Animacy

Language can be dehumanizing towards other people, sure. That almost seems obvious. But the language we use can also devalue and denigrate the air we breath, the ground we walk on, the birds that wake us in the morning.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist who is part of the Potawatomi Nation, wrote about her experience learning Potawatomi. When she wrote Braiding Sweetgrass, there were only nine fluent speakers left. She went to see them speak, noticed the way the language mirrored the living world around them.

Robin says “English is a noun-based language, somehow appropriate to a culture so obsessed with things. Only 30% of English words are verbs, but in Potawatomi, that proportion is 70%.”

In Potawatomi, you don’t say “it’s Saturday.” You say “to be a Saturday.” You don’t say “it’s a bay.” You say “to be a bay.” Grammatically, this confused and frustrated Robin until she understood the wisdom pulsing through the grammar.

“A bay is a noun only if water is dead… But the verb wiikwegamaa - to be a bay- releases the water from bondage and lets it live…to be a hill, to be a sandy beach, to be a Saturday, all are possible verbs in a world where everything is alive. Water, land, and even a day, the language a mirror for seeing the animacy of the world.”

Using language in this way expands our understanding of love and respect. We can’t just take care of ourselves and call that culture.

Sure, my identity as one person is not static. I should have the words to reflect and hold my changing states. But I should have the words to extend that liberation to all living things around me. And I like the idea of expanding my definition of aliveness.

Referenced in this episode:

Lingthusiasm:

I go into much more detail in the full video/audio podcast but I wanted to experiment with sharing my findings in a written format, for those of you that prefer to think this way!

(promise after this i'll stop recommending babel by rf kuang but) babel by rf kuang is the gateway drug to linguistic fascination - highly recommend, excited to listen to this episode!

The written notes are great for quick reference! I appreciate them.

To xpost from my YouTube comment: You stirred me toward research! A couple of interesting, disconnected notes.

Irish metaphors surrounding time are more complicated than simply being "storyteller, not money." This is likely due, in part, to cultural cross-pollination with ideas from English. (We see Irish-language metaphors that parallel the English "time is money" idea.) The most intriguing detail I discovered is that the Irish word for time is identical to the Irish word for "weather," with the "weather" usage being dominant in most cases. The idea that the time and the weather are the same thing (that time is seen, tracked, or experienced in a way tethered to weather and seasonal patterns) is fascinating to me, and implies a conception of what time is that extends even deeper into how we frame the very idea. (I also found that determining Irish language trends is harder than one might expect, because the language is highly divided by region, with metaphors being distinct in different regional dialects.)

On the detection of earth's magnetic field in the Gurindji people: I was so skeptical of your claim at first! But, yes, it turns out Meakins' work bears this out. The nuance that surprised me is: It turns out a portion of the population of ALL humans can detect changes in the magnetic field. It's just, for English speakers, there's no ability to describe what the perceived data means, even though we can see brain changes in participants. It's input data that can't be translated. But for the Gurindji people, who are so attuned to direction? They can translate the data into meaning.

I will broadly say: I'm an English instructor with some background in linguistics. My understanding is that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has largely been set aside in its "strong" form (where we say that language unilaterally shapes or determines what we can think or how we can frame things), but a "soft" form is still widely seen as viable (where language and culture have a bidirectional influence on one another and where certain framings/conceptions are more accessible based on the language we use).

And since writing the above notes, I've also been thinking about other entrenched metaphors in my thinking. I'm especially considering how time is conceptualized as a finite resource (whether we strictly view that as money or not), rather than as something more open and experiential -- like a landscape, a canvas, a storyteller (as in the Irish proverb), or some other form of opportunity space. Still mulling that over, but there are ways I want to push back against some of this time-as-finite-resource framework. However much it's down to language vs culture, I find it hard to see time as anything other than a burden, an obligation, something that proves my insufficiency as I continually fail to use it well enough. I feel like there's a more experiential way to engage with it, and those experiential framings are obscured my the norms of my language.